Death dates.

If you want to be a serious student of anything that requires knowledge of history, you cannot avoid memorizing dates for long. At some point it catches up to you.

I recall years ago being dumbstruck in classes and seminars that Prof. Jonathan Brown was able to recall with such ease the death dates of countless historical figures and events. A few years later, my dear friend and colleague Ust. Tariq Patanam told me a story of a discussion he had with our teacher at the time who was able to criticize a claim purely on the basis of recognizing an anachronism. Our teacher, he told me, casually prepared and stirred his tea and proceeded to dismantle an argument by observing, quite simply, that one of the figures lived prior to the other and could not have said what he was reported to have said.

Keeping track of death dates and the regions in which historical figures were active is an integral part of being a student of knowledge. It is not the sole purview of hadith scholars, but it extends to all forms of knowledge wherein ideas are developed over centuries and an eye for detail proves necessary in maintaining the high level of critical engagement expected of students of knowledge by the great scholars and sages in whose large footsteps we follow.

Perhaps one of the greatest benefits for the student who reads and peruses Arabic works is the ability to identify when quotes end. There are times where judgments are made about the words cited but given the lack of quotations in manuscript and earlier print works and the inconsistency of those quotations in contemporary print, knowledge of the chronological and geographical arrangement of texts and figures proves invaluable.

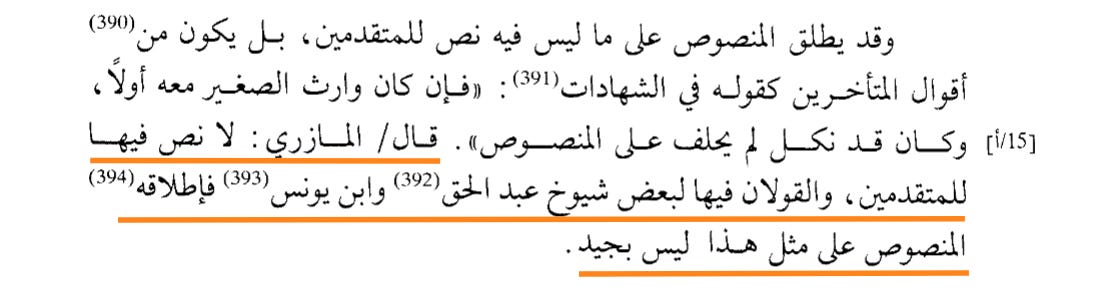

The image above contains a paragraph taken from Ibn Farḥūn's (d. 799/1396 AH) introduction to his commentary on Ibn al-Ḥājib's (d. 646/1249) compendium of Mālikī law titled Jāmiʿ al-ummahāt.

After citing the words of Ibn al-Ḥājib, rendered by the editor in parantheses, Ibn Farḥūn quotes al-Māzarī with no punctuation indicating whether al-Māzarī's statement ends or continues to period. The words, underlined above, read:

"Al-Māzarī said: there exists no record concerning [the aforementioned legal case] among the ancients (mutaqaddimīn), the two opinions concerning it belong to some of the teachers (shuyūkh) of ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq and Ibn Yūnus, therefore his use of the term manṣūṣ (recorded case) to refer to [a case] like this is not proper."1

A reader would be excused for assuming that the phrase "his use of the term manṣūṣ...is not proper" belongs to al-Māzarī. However, al-Māzarī died in 536 AH, some 34 years before 570 AH when Ibn al-Ḥājib was born. There is no way he could have commented on the text. Thus, it has to be Ibn Farḥūn who provided that comment. Furthermore, one may take an educated guess that the citation of the two Sicilian masters, ʿAbd al-Ḥaqq (d. 466/1073) and Ibn Yūnus (d. 451/1059-60), is a continuation of the claim by al-Māzarī that no recorded case exists among the ancients. By citing scholars who lived after the terminus ante quem2 of the generation of the ancients, those labeled the “latter-day” scholars (mutaʾakhkhirīn), al-Māzarī would be completing the claim. That said, given the ambiguity and lack of punctuation, the phrase can also be read as the start of Ibn Farḥūn comment on the cited case by Ibn al-Ḥājib in the context of al-Māzarī’s claim.

All said, there are no mechanisms for ensuring that readers are made aware of any of these details. Moreover, to expect editors to keep in mind the death dates of authors as they churn out book after book is unrealistic. Rather, it becomes the responsibility of the student to maintain this record in their mind to facilitate reading and engaging with the corpus that constitutes the intellectual history of a complex and vibrant tradition.

Examples like this are to be found everywhere. Though starting the process of memorizing names, dates, and places can be daunting, repetition can prove to be a student's best friend. The more one associates a date or place with an author when encountering their name, the more likely this will be reinforced in the absence of rote memorization. This can be done by always reading the covers of books and pausing at the names and death dates of authors, even if the authors and the works are familiar.

One can also actively memorize these details through study. I once met Prof. Brown in his office and found him sitting on the ground with ziploc bags of small notecards. I asked him what they were, and he proceeded to show me they contained names, dates, and places associated with various famous and obscure figures in history. Alongside these notes were details related to events, works, concepts, etc. Behind the veil of a vast storehouse of information and knowledge lies the diligent and painstaking work of consistent review.

We are not taught the means to achieve mastery through our school education anymore. It falls on us to find whatever avenues of inspiration that God affords us in our lives. What impresses you about a person's knowledge or abilities of recall is often a function of you not having gone through the process to get where they are. It is imperative to be open to inspiration and to not be shy to ask those who have mastered some skill for their advice and guidance. Even those younger and less experienced than you have so much to offer. Then once you embark on that journey, even if your source of inspiration has a headstart on you and your competitive drive counterintuitively beckons you to abandon hope, you'll eventually find yourself at a station previously thought impossible to reach and thanking Allah for demystifying something you initially mistook as an impossible feat.

Allah grant us the ambition to seek knowledge to the Pleiades.

Burhān al-Dīn Ibrahīm Ibn ʿAlī Ibn Farḥūn, Kashf al-niqāb al-ḥājib min muṣṭalaḥ Ibn al-Ḥājib, ed. Hamzah Abū Fāris and ʿAbd al-Salām al-Sharīf (Beirut: Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmī, 1990), 100.

This is a fancy Latin term for “the latest possible date.” The terminus ante quem of the generations of the ancients (mutaqaddimīn) is said to be 386/998, the death date of Ibn Abī Zayd of Kairouan, author of the famous Mālikī primer, the Risālah.