Ibn Ḥajr's Marginalia Notes on Concerns of Plagiarism (or Unreferenced Borrowings)

Imagine having read so many works in your life that you're able to recall passages that seem eerily alike and thus verify instances of unreferenced borrowing by cross-comparing texts.

The masterful 10th/15th century ḥadīth scholar and historian, Shams al-Dīn al-Sakhāwī (d. 902/1497), composed a tome of a biography on his teacher, the inimitable Ibn Ḥajr al-ʿAsqalānī (d. 852/1449). In it, he includes some of the notes that Ibn Ḥajr etched on the margins of texts he possessed. Among these marginalia are comments on unmentioned borrowings in various works1.

Al-Sakhāwī compiles these, from Ibn Ḥajr's own handwriting, and reproduces them in an entire section titled:

"Concerning those who took the composition of others, claimed it as their own, while adding very little and leaving out [some], yet retaining most of the exact phrasing of the original."

This list is quite damning and includes the following examples:

(1) Abū Yaʿlā's al-Aḥkām al-sulṭāniyyah is mostly taken from the Shāfiʿī al-Māwardī's book of the same name. The only difference is that Abū Yaʿlā constructs the work on the basis of his own madhhab—that of Aḥmad Ibn Ḥanbal.

(2) Al-Taymī's commentary on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī is copied from Ibn Baṭṭāl's.

(3) Al-Baghawī's Sunan is taken from two earlier sources.

(4) Ibn Mulaqqin's biographical dictionary is a near replica of al-Subkī's. Ibn Ḥajr says he compared the texts side-by-side and found them to be nearly identical with some minor differences. This is after having criticized Ibn Mulaqqin for doing the same with a commentary on Bukhārī. (Mind you, Ibn Mulaqqin was one of Ibn Ḥajr’s teachers…)

Al-Sakhāwī writes that Ibn Ḥajr had read so many texts to various scholars that he would get excited when a student would ask to read one of those texts which he had read which were of lesser interest to the common student. Al-Sakhāwī recounts the joy of his teacher when he asked to read such texts with him.2

Like other great ḥuffāẓ—masters of ḥadīth who had memorized inconceivable quantities by modern standards—he would write while listening to a student recite ḥadīth to him. Once the Mālikī judge Badr al-Dīn al-Tanasī (d. 835/1431), a chief qāḍī in Egypt, recounts having doubts about whether Ibn Ḥajr was paying attention to him as he recited to him from a ḥadīth compilation.3 He was discomforted by the possibility and was unable to avert such thoughts; it drove him to test the attentive capacity of his sheikh. He decided he would intentionally leave out a portion of a ḥadīth. Upon doing so, Ibn Ḥajr immediately raised his head, lowered his pen, and instructed him to repeat the ḥadīth again. After al-Tanasī had correctly recited the ḥadīth, Ibn Ḥajr return to writing.4

After describing the daily routine of his teacher, al-Sakhāwī

notes the following about Ibn Ḥajr:

“All of his time was filled with worship—either through knowledge, prayer, recitation, or supplication.”5

May Allah be pleased with our beloved masters Ibn Ḥajr and al-Sakhāwī and all our predecessors, known and unknown, who have gone before us.

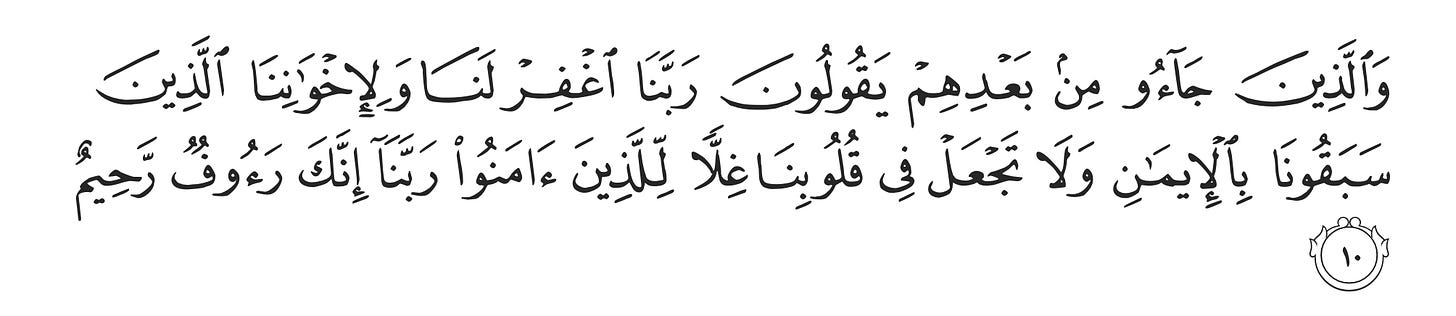

And those who come after them will pray, “Our Lord! Forgive us and our fellow believers who preceded us in faith, and do not allow bitterness into our hearts towards those who believe. Our Lord! Indeed, You are Ever Gracious, Most Merciful.”

Shams al-Dīn al-Sakhāwī, Al-Jawāhir wa l-durar fī tarjamat Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Ḥajr (Beirut: Dār Ibn Ḥazm, 1999), 390-1. Similar stories are mentioned about al-Mizzī (by Ibn Kathīr), al-Daraquṭnī, and other

al-Sakhāwī, al-Jawāhir, 241.

al-Sakhāwī, al-Jawāhir, 394-5. As for the name of the person reciting to Ibn Ḥajr in the story: if it is indeed Badr al-Dīn al-Tanasī—and not al-Ḥāfiẓ al-Tanasī (d. 833/1430)—then he was the student of Shams al-Dīn al-Bisāṭī (d. 842/1438) and took over his seat as Mālikī qaḍī, before eventually rising to chief qāḍī or qāḍī al-quḍāh. Among his academic accolades, he received ijāzah from Ibn ʿArafah. As for al-Ḥāfiẓ al-Tanasī, he was the student of Ibn Marzūq al-Ḥafīd and teacher of Sīdī Aḥmad Zarrūq. Regarding the epithet, Ténès is a coastal city in the north of Algeria which has been continuously inhabited since its founding as an ancient Phoenician port around the 8th century B.C.

Similar stories are mentioned about al-Mizzī (by Ibn Kathīr), al-Daraquṭnī, and others. See al-Sakhāwī, al-Jawāhir, 395-8.

al-Sakhāwī, al-Jawāhir, 1053.

Saw this program and thought of your work: https://al-furqan.com/events/paleographical-aspects-of-islamic-manuscripts-script-and-calligraphy-styles-and-usage/

Really interesting. In English, the first appearance of "plagiary" was in 1601, "plagiarism" in 1621, "plagiarist" in 1674 and "plagiarize" in 1716 (see Polymath by Peter Burke); e.g. largely coincided with the development of intellectual property law, which changed the system of knowledge production in the west. This would put the Islamic tradition 200ish years ahead of at least English. Interesting, thanks for sharing!